|

Behavioral Science Response to COVID-19 Working Group

COVID-19 and Behavioral Science

The spread of COVID-19 is, in part, based on human behavior. Behavioral scientists are a unique resource for changing human behavior in ways that may reduce the spread of the virus. The Psychonomic Society initiated an effort to assemble a group of experts in learning and behavior modification. Our goal is to disseminate evidence-based recommendations in areas where behavioral science may make a unique contribution.

Resources to Slow the Spread of COVID-19

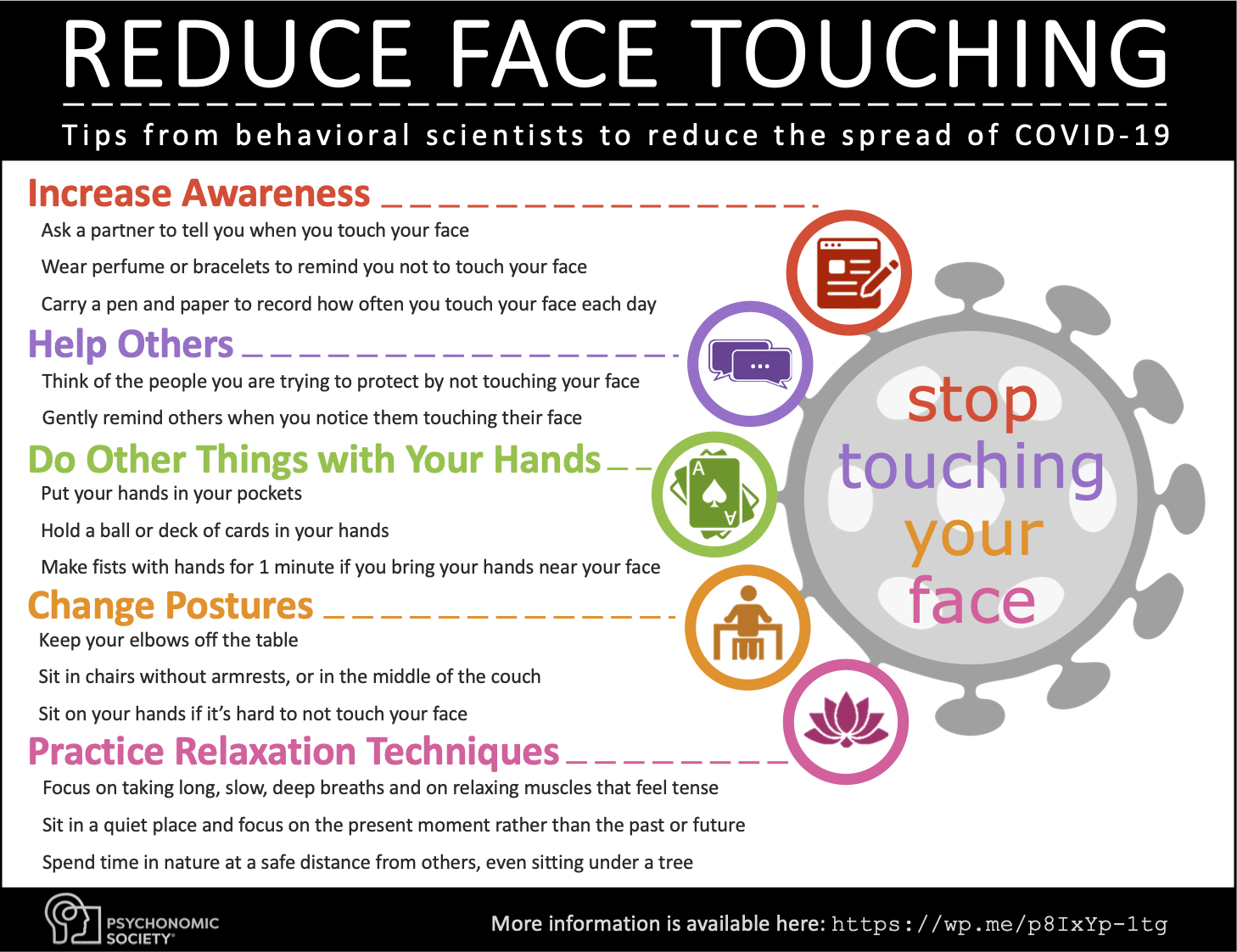

1. How to Reduce Face Touching Our infographic on How to Reduce Face Touching is the first resource produced by the Working Group. The infographic, as seen below, is now available in 20+ languages. View, download, and share!

Download the PDF

(PDF available in 20+ languages)

2. Practical Tips for Social Distancing Over time, stay-at-home orders are likely to be gradually lifted in many

localities. In this context, it is more important than ever that we

strengthen our ability to successfully social distance. The following infographic provides practical information on why social distancing matters and how to practice conscientious social distancing in public environments. View, download, and share!

Download the PDF

(PDF available in 20+ languages) 3. Hand Washing

The novel coronavirus spreads through human interactions with people who are infected. Therefore, changing human behavior is a powerful, low cost, immediate intervention to stem the pandemic. Our latest infographic provides evidence-based recommendations to promote hand washing. View, download, and share!

Download the PDF

(New translations coming soon)

About the Behavioral Science Response to COVID-19 Working Group

The

Psychonomic Society is launching new initiatives to respond to

COVID-19. The first was originally directed toward reducing the carbon

footprint of the society, in part by adapting our annual meeting to a

hybrid or even purely virtual format, thereby curtailing

carbon-intensive airplane travel. Now, the rapid rise of the pandemic

makes a virtual conference even more pressing. Remotely accessible

conferences offer further advantages by opening up our meeting to people

who live far away from the meeting venue or who lack the means or the

time to travel because of family or other obligations. Virtual meetings

are also far more inclusive for those with disabilities, for whom

physical attendance is especially challenging.

This

latest initiative capitalizes on the extensive expertise in behavioral

science within our membership. The coronavirus spreads through human

behavior, and so it can best be contained if we teach people best

practices for how to change critical behaviors such as their

hand washing, social distancing, and in this instance, face touching.

Research has shown that we touch our faces far more often than we may

realize, about 23 times per hour, and this creates a major path for the

spread of the infection. We

live in a world filled with misinformation, myths, and misguided

advice, often offered with good intentions but limited knowledge about

the science of pandemics. The recommendations we give here on how to

reduce face touching is based on what we know to be true from

published studies, or in some cases on what we believe is extremely

likely to be true, based on findings regarding similar behaviors. With

the help of our colleagues, we hope to extend this first effort with

further messages addressing other behaviors, such as hand washing and

social distancing, that play a key role in the transmission of COVID-19.

References (How to Reduce Face Touching)

Our evidence-based recommendations to reduce face touching are based on the following references: - Ellingson, S. A., Miltenberger, R. G., Stricker, J. M., Garlinghouse, M. A., Roberts, J., Galensky, T. L., & Rapp, J. T. (2000). Analysis and treatment of finger sucking. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33(1), 41-52. http://doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-41

- Ghanizadeh, A., Bazrafshan, A., Firoozabadi, A., & Dehbozorgi, G. (2013). Habit Reversal versus Object Manipulation Training for Treating Nail Biting: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Iranian journal of psychiatry, 8(2), 61-67. PMCID: PMC3796295

- Long, E. S., Miltenberger, R. G., Ellingson, S. A., & Ott, S. M. (1999). Augmenting simplified habit reversal in the treatment of oral-digital habits exhibited by individuals with mental retardation. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 32(3), 353-365. http://doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-353

- Miltenberger, R. G., Fuqua, R. W., & Woods, D. W. (1998). Applying behavior analysis to clinical problems: review and analysis of habit reversaL. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 31(3), 447-469. http://doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-447

- Rapp, J. T., Miltenberger, R. G., & Long, E. S. (1998). Augmenting simplified habit reversal with an awareness enhancement device: preliminary findings. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 31(4), 665-668. http://doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-665

- Stricker, J. M., Miltenberger, R. G., Garlinghouse, M. A., Deaver, C. M., & Anderson, C. A. (2001). Evaluation of an awareness enhancement device for the treatment of thumb sucking in children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 34(1), 77-80. http://doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-77

- Twohig, M. P., & Woods, D. W. (2001). Evaluating the duration of the competing response in habit reversal: a parametric analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 34(4), 517-520. http://doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-517

- Woods, D. W., & Miltenberger, R. G. (1995). Habit reversal: A review of applications and variations. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 26(2), 123-131. http://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7916(95)00009-O

- Woods, D. W., Murray, L. K., Fuqua, R. W., Seif, T. A., Boyer, L. J., & Siah, A. (1999). Comparing the effectiveness of similar and dissimilar competing responses in evaluating the habit reversal treatment for oral–digital habits in children. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 30(4), 289-300. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7916(99)00031-2

Additional sources of information:

https://www.apa.org/practice/programs/dmhi/research-information/pandemics

References (Practical Tips on Social Distancing)

The following are many of the references to the scientific papers that informed our recommendations on social distancing:

- Atkinson, J., Chartier, Y., Pessoa-Silva, C.L., Jensen, P., Li, Y.,

Seto, W.-H. (Eds). (2009). Natural Ventilation for Infection Control in

Health-Care Settings. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

ISBN 978 92 4 154785 7 (NLM classification:WX 167)

- Block, P., Hoffman, M., Raabe, I. J., Dowd, J. B., Rahal, C.,

Kashyap, R., & Mills, M. C. (2020). Social network-based distancing

strategies to flatten the COVID 19 curve in a post-lockdown world. arXiv

preprint arXiv:2004.07052.

- Cialdini, R.B. (2001). Harnessing the Science of Persuasion. Harvard Business Review, October 2001, Reprint r0109d.

- Cialdini, R.B. (2006). Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, Revised Edition. Harper Business.

- Cialdini, R. B. (2020). Reducing Undesirable COVID-19 Behaviors. https://www.influenceatwork.com/inside-influence-report/advice-for-reducing-undesirable-covid-19-behaviors/

- Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: strong effects of simple plans. American psychologist, 54(7), 493. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.493

- Linkenauger, S. A., Bulthoff, H. H., & Mohler, B. J. (2015).

Virtual arm’s reach influences perceived distance but only after

experience reaching. Neuropsychologia, 70, 393–401. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.10.034.

- Linkenauger, S. A., Leyrer, M., Bülthoff, H. H., & Mohler, B. J.

(2013). Welcome to wonderland: the influence of the size and shape of a

virtual hand on the perceived size and shape of virtual objects. PloS

one, 8(7), e68594. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068594

- Liu, L. L., & Park, D. C. (2004). Aging and medical adherence:

the use of automatic processes to achieve effortful things. Psychology

and aging, 19(2), 318. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.318

- Locey, M. L., & Rachlin, H. (2015). Altruism and anonymity: A behavioral analysis. Behavioural Processes, 118, 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2015.06.002

- Jones, B. A., & Rachlin, H. (2009). Delay, probability, and

social discounting in a public goods game. Journal of the Experimental

Analysis of Behavior, 91(1), 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2009.91-61

- Martin S. J., Goldstein, N., & Cialdini, R. B. (2014), The small

BIG: small changes that spark big influence. Grand Central Publishing.

- McFarland, C., & Glisky, E. (2012). Implementation intentions and

imagery: Individual and combined effects on prospective memory among

young adults. Memory & cognition, 40(1), 62-69. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-011-0126-8

- Parshina-Kottas, Y., Saget, B., Patanjali, K., Fleisher, O.,

Gianordoli, G. (2020). This 3-D simulation shows why social distancing

is so important. The New York Times, April 14. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/14/science/coronavirus-transmission-cough-6-feet-ar-ul.html

- Proffitt, D. R. & Linkenauger, S. A. (2013). Perception viewed as

a phenotypic expression. In: Action science: Foundations of an emerging

discipline, ed. W. Prinz, M. Beisert & A. Herwig, pp. 171–98. MIT

Press.

- Stevens, H. (2020). Why outbreaks like coronavirus spread

exponentially, and how to “flatten the curve”. Washington Post, March. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/world/corona-simulator/

- Yang, S., Lee, G.W.M., Chen, C.-M., Wu, C.-C., Yu, K.-P. (2007). The

size and concentration of droplets generated by coughing in human

subjects. Journal of Aerosol Medicine, 20(4), 484-494.

- Witt, J. K., Proffitt, D.R., & Epstein, W. (2005). Tool use

affects perceived distance but only when you intend to use it. Journal

of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 31,

880-888.

- World NHK-Report, SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus Micro-droplets, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vBvFkQizTT4

Additional sources of information:

American Psychological Association

Questions?

Contact Member Services at info@psychonomic.org or +1 847-375-3696.

|

|

COVID-19

Working Group

Jonathon Crystal

Indiana University Bloomington, USA

(Chair)

James Pomerantz

Rice University, USA

(Co-Chair) Kate Bruce

University of North Carolina Wilmington, USA

Andy Delamater

Brooklyn College, USA Claudia Dozier

University of Kansas, USA

Wayne Fuqua

Western Michigan University, USA Mark Galizio

University of North Carolina Wilmington, USA Rachel Jess

University of Kansas, USA

Megan Heinicke

Sacramento State University, USA Debbie Kelly

University of Manitoba, Canada Sachiko Koyama

Indiana University Bloomington, USA

Olga Lazareva

Drake University, USA Linda LeBlanc

LeBlanc Behavioral Consulting, USA Mark McDaniel

Washington University in St. Louis, USA

Laura Mickes

University of Bristol, UK Raymond Miltenberger

University of South Florida, USA

Matthew Normand

University of the Pacific, USA

Amy Odum

Utah State University, USA

Danielle Panoz-Brown

Indiana University Bloomington, USA Gordon Pennycook

University of Regina, Canada

Penny Pexman

University of Calgary, Canada Suparna Rajaram

Stony Brook University, USA

Phil Reed

Swansea University, UK

Crystal Slanzi

University of Florida, USA

Carole Van Camp

University of North Carolina Wilmington, USA

Tim Vollmer

University of Florida, USA

Wendy Donlin Washington

University of North Carolina Wilmington, USA

Jessica Witt

Colorado State University, USA

Doug Woods

Marquette University, USA

|